When I was in seminary, my mother sent me a poem for Good Friday. It is called “Old Tears in Galilee”, and was written by Georgia Starbuck Galbraith.

No woman has ever borne a child,

And worshipped his eyes and the way he smiled,

And reacted with pride at his first clear word;

Who bound up his hurts and loved his absurd

Fierce concentration, watching a spider;

Who saw him grow till he stood beside her,

Straight and tall as a mountain pine;

No woman who had a son like mine

Ever believed that aught than good

Could come to this fruit of her motherhood—

No woman ever believed—not I!

That this life of her life was born to die

As mine, going down from Nazareth

to Jerusalem and sorrow and death.

Some say he was wrong, some say he was right

In the way he did that dark spring night.

I only know what is done is done,

And I weep for Judas ... I weep for my son.

The first time I read this poem, I wept. It forced me with a stunning and sudden shock to see Judas the Ultimate Traitor as having been, at one time, a loved human being. I had never seen him that way before, but I knew then that if his mother had seen him so, this is undoubtedly how Jesus had seen him.

There are two accounts in the New Testament of how Judas Iscariot met his end. Matthew’s Gospel tells us that he hanged himself (Matthew 27:5); Luke says that he fell down and burst open (Acts 1:18). Whatever the manner of his death, it is clear that Judas died at the same time Jesus did.

It is generally assumed that Judas is forever condemned and lost. Jesus said, “Woe to that man by whom the Son of man is betrayed. It would have been better for that man if he had not been born” (Matthew 26:24). There can indeed be no doubt that it would have been better not to have lived at all than to live through the events of Jesus’ last night, knowing that you were responsible for putting those events into motion. But this feeling of terrible anguish to the point of self-destruction could be possible only if you truly loved the one you had betrayed.

We are nowhere in the Bible given a reason for Judas’ decision to betray Jesus. Luke and John attribute it to Satan’s entering into him. One or two writers have surmised that it was a misguided effort to force Jesus’ hand to reveal himself as the Messiah through a supernatural intervention. Whatever the reason, it is probable that Judas did not dislike Jesus, nor was he out to “get him,” nor I think was he out to earn an easy thirty silver pieces—if any of these possibilities had been true, he would not have angrily thrown the money down in the temple after he saw how he had been used by the authorities.

Judas was one of the Twelve; he did not leave off from following Jesus during the three years of public ministry when many others did; he was almost certainly one of the seventy trusted followers sent out on a successful mission to preach, heal, teach, anoint the sick, and cast out demons. Judas received the piece of bread dipped in the bowl at the Last Supper—traditionally a sign of affection. And Judas identified Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane with a kiss, a sign possible because the embrace or kiss might have been a familiar gesture for him—he may have kissed Jesus often.

One can only wonder at what Judas was thinking and feeling at the Last Supper, knowing that he had already set events in motion that would lead to Jesus’ arrest. As the account in Matthew says,

When evening came, Jesus was reclining at the table with the Twelve. And while they were eating, he said, “I tell you the truth, one of you will betray me.”

They were very sad and began to say to him one after the other, “Surely not I, Lord?”

Jesus replied, “The one who has dipped his hand into the bowl with me will betray me. The Son of Man will go just as it is written about him. But woe to that man who betrays the Son of Man! It would be better for him if he had not been born.”

Then Judas, the one who would betray him, said, “Surely not I, Rabbi?” Jesus answered, “Yes, it is you.” (Matthew 26:20-25)

What was going through his mind as he came to the Passover table with the other disciples and Jesus presiding? Surely a chill must have gone through him when Jesus said, “Yes, it is you.” And yet he still dipped the bread, and then went out into the night to keep his assignation. Why? Who knows? No one on earth, then or now, but Judas himself.

We cannot overlook Judas’ sin. He betrayed Jesus, who was his Lord and his friend. He did not trust or understand Jesus at the end. He left him in the middle of the Last Supper where he had been made welcome, and never saw the others again except in the Garden of Gethsemane, and then not to speak to them.

Judas was a weak person at a time when strength was called for. Of course, he was not alone in that. Peter denied Jesus publicly three times after saying he would go with Jesus even to death. When Jesus was determined to return to Bethany near Jerusalem where his life had recently been threatened, Thomas said, “Let us also go, that we may die with him (John 11:16), but he joined all the others who fled in the Garden, leaving Jesus to his fate. They all fled. Judas was merely the weakest knot in a net of weaklings.

But Judas was loved by someone—his mother at least, if we consider the poem with which this sermon began. Presumably he had friends among the disciples. He was entrusted with the money box by Jesus. He must have been concerned about the poor, misguided though that concern may have been at times. He was close enough to Jesus at the Last Supper to have received the bit of bread. Above all, Jesus loved him.

When he saw the consequences of his actions, he was outraged. It is easy to guess that he had never intended that Jesus die. He went to the Temple authorities, proclaimed that Jesus was innocent, threw down the silver in fury, shame, guilt, despair, and anguish. The words of Matthew’s Gospel are, “He repented and brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and the elders, saying, ‘I have sinned in betraying innocent blood’” (Matthew 27:3-4). Judas said, “I have sinned.” He repented. These are words of remorse—perhaps even salvation.

Judas bears not only his own name. He bears the name of his people: Judah, the Jews. But he could just as well have been named Adam. He bears the stigma of the human race. He represents all Jewish and Gentile, all human unbelief, half-belief, misunderstanding, failure, and betrayal. All people are like Judas. The Bible is unequivocal about that.

The entire human race is marked by sin: “The Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. And the Lord was sorry that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart” (Genesis 6:5-6).

Paul wrote: “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23).

Jesus said: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not” (Luke 13:34).

Judas is one sinner among a raceful of sinners: “Then Satan entered into Judas called Iscariot, who was of the number of the twelve; he went away and conferred with the chief priests and captains how he might betray [Jesus] to them” (Luke 22:3-4).

Judas was not special among human beings, except in that his sin was pivotal for the salvation of sinners. His story is the story of every tragic failure of someone who lets down those who love them, of potential horribly lost at the last minute when the potential was greatest and the stakes highest.

Judas was chosen by Jesus and numbered among the twelve—as John says, Jesus “knew all men and needed no one to bear witness of man; for he himself knew what was in man” (John 2:25). Judas’ fury in his last hour obviously shows that he became aware of his failure and knew that it was great. His perception of the immensity of his failure is the measure of the greatness that he knew could have been his, and is therefore the measure of the vast despair to which he succumbed.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, in his great work The Brothers Karamazov, said, “The secret of man’s being is not only to live but to have something to live for.” When Judas fell from grace, he lost his reason to live—this was possible only because Jesus had been his reason to live. Judas made a bad decision and then knew that he had chosen emptiness. This is the state of the human race apart from God: emptiness, meaninglessness, despair.

When Jesus said to the disciples, “I tell you the truth, one of you will betray me,” they all asked, “Surely not I, Lord?” Each one believed that he might do so. Judas is unique not in his sin, but only in what his sin did.

And it is for this that Jesus came to be born, and to die, and to rise again. On Good Friday, the price of our salvation was paid. What made that price necessary is human sin, the sin of all people. The sins we ourselves commit. As our lesson from Isaiah said,

“He was wounded for our transgressions;

he was crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace,

and with his stripes we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray;

we have turned—every one—to his own way;

and the Lord has laid on him

the iniquity of us all. (Isaiah 53:5-6)

We know of the resurrection and the salvation. We know that when Jesus overcame the sharpness of death, he opened the kingdom of heaven to all believers. The Gospels repeatedly say that the disciples understood various integral matters only after the resurrection. The burden of our sins is perhaps easier for us who know of the resurrection, though it ought not to be.

Judas did not know of the resurrection. He knew only the tragic death of Jesus and that he had been solely responsible for it. Jesus asked those who arrested him why they had not arrested him while he was in the Temple teaching openly. This question indicted them in their cowardice, for they wanted only to take him in the darkness, without witnesses, without any possibility of the crowds of people who loved him from rising up. So Judas’ betrayal was essential; he, and only he, could lead them to where Jesus would be at night, when there would be no crowds.

We who claim salvation in the name of Jesus are like Judas, his failed disciple. We have walked with Jesus devotedly, coming to church and giving money and serving in high places, but when we are put to a test, we have at times defaulted to worldly standards and believed and acted as if there were no such thing as faith. We have at times walked in the ways of the world rather than according to the will and command of Jesus.

At times we also have “stolen from the money box” by squandering the gifts which the Lord has entrusted to us, using them selfishly rather than for God’s glory. We also at times have refused to sit at the table with the saints, but rather, even after being given the sign of affection (a bit of bread from his own altar), we have preferred to get up and walk out into the night, alone, on our own errands. We also at times have “kissed the Lord” in sham affection for our own selfish purposes, rather than offered a full embrace of heartfelt, sacrificial love.

Above all, when our sins confront us and forgiveness is offered, we have at times preferred self-pity and despair, thinking ourselves beyond even the love and forgiveness of God. Surely this is the greatest sin that Judas committed—thinking himself beyond forgiveness. And this is one of the most pervasive sins in the human condition. I have found it often in the hearts of Christians. I have seen it at times in my own heart.

But our inheritance is the forgiveness of sins and salvation, the peace of God that passes understanding. Good Friday’s cross for Jesus meant death, but for us it means life. It is reconciliation with God for all sinners who look to him for forgiveness. While on the cross, Jesus prayed, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). For whom did Jesus beg this forgiveness? The soldiers who wielded the hammer and nails? The members of the Jewish council who turned him over to the Romans? Pilate, who condemned him? Could the prayer have included Judas, who was the pawn of these authorities? The Biblical witness is clear that Judas, among all those who had a part in Jesus’ death, clearly “did not know what he did.” In fact, is there anyone for whom Jesus was not praying at that time?

Regarding the fate of Judas, George MacDonald wrote, “Must we believe that Judas, who repented even to agony, who repented so that his high-prized life, self, soul became worthless in his eyes and met with no mercy at his own hand—must we believe that he could find no mercy in such a God [as ours]? I think, when Judas fled from his hanged and fallen body, he fled to the tender help of Jesus, and found it—I say not how. He was in a more hopeful condition now than during any moment of his past life, for he had never repented before. But I believe that Jesus loved Judas even when he was kissing him the traitor’s kiss; and I believe that he was his Savior still.” [Unspoken Sermons, quoted in The Wind from the Stars, edited by Gordon Reid, Harper Collins, 1992, selection number 173]

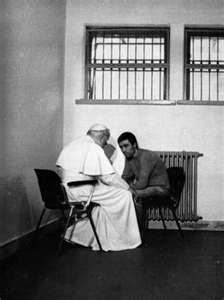

On May 13, 1981 a Muslim assassin named Mehmet Ali Agca shot Pope John Paul II four times during a public appearance in the square outside the Vatican. Though the assassin’s intentions was obviously to kill, the Pope survived. The assailant was arrested, tried, and sentenced to a 19-year term in an Italian prison. Two years after the assassination attempt, the Pope visited the man who shot him. No one knows for sure what transpired between the men, other than that the Pope forgave his assailant. Here is one example of Christian mercy shown to a great sinner, a mercy that overwhelms great sin, showing a pattern that began with Jesus.

On May 13, 1981 a Muslim assassin named Mehmet Ali Agca shot Pope John Paul II four times during a public appearance in the square outside the Vatican. Though the assassin’s intentions was obviously to kill, the Pope survived. The assailant was arrested, tried, and sentenced to a 19-year term in an Italian prison. Two years after the assassination attempt, the Pope visited the man who shot him. No one knows for sure what transpired between the men, other than that the Pope forgave his assailant. Here is one example of Christian mercy shown to a great sinner, a mercy that overwhelms great sin, showing a pattern that began with Jesus.

I have heard a folk tale that offers an answer to the question of the eternal destiny of Judas. According to this tale, a long time after Judas’ death, he gradually came to consciousness and found himself in utter darkness, lying flat on his face on dank ground oozing with filth. He was exhausted. For a thousand years he lay there, agonizing over what he had done. Then with a groan he rolled over. He saw a tiny point of light away high above him, and he realized that he was in a deep, deep pit—a hole with sheer sides made of slime and mud. For three thousand years he contemplated that hole and the pinpoint of light high up. Then he dragged himself to his feet and began to try to climb out. For five thousand years he climbed, groping upward and sliding back down. At the end of the five thousand years his hand gripped the top edge of the hole, and he pulled himself out and lay gasping on the ground above. After a thousand years he had regained his strength and looked up. He saw Jesus and the Eleven, sitting at table, radiant with glory. There was one seat vacant. Jesus said, “What took you so long?”

It is only a story. We don’t know, and cannot know, what Judas’ eternal destiny is. It is not really our business. Jesus, probably referring to Judas, says that “the son of perdition” is lost “that the scripture might be fulfilled” (John 17:12), but even this passage does not make clear the irrevocable condemnation of the son of Simon Iscariot. Peter said merely that Judas “turned aside, to go to his own place” (Acts 1:25). What these things mean, what Judas’ eternal destiny is, is not our business.

But it is obvious that the story of Judas is also the personal story of each Christian and every human being. And this is our business.

No woman has ever borne a child,

And worshipped his eyes and the way he smiled,

And reacted with pride at his first clear word;

Who bound up his hurts and loved his absurd

Fierce concentration, watching a spider;

Who saw him grow till he stood beside her,

...

Some say he was wrong, some say he was right

In the way he did that dark spring night.

I only know what is done is done,

And I weep for Judas ... I weep for my son.

The story of Judas is the story of horrible sin and sacrificial love, forgiveness, and reconciliation—the true story in which Jesus’ love is proven stronger than the worst sin of all time. That is everyone’s business. In the end it is the only business that matters.